on the desire to be loved

notes from a recovering hopeless romantic

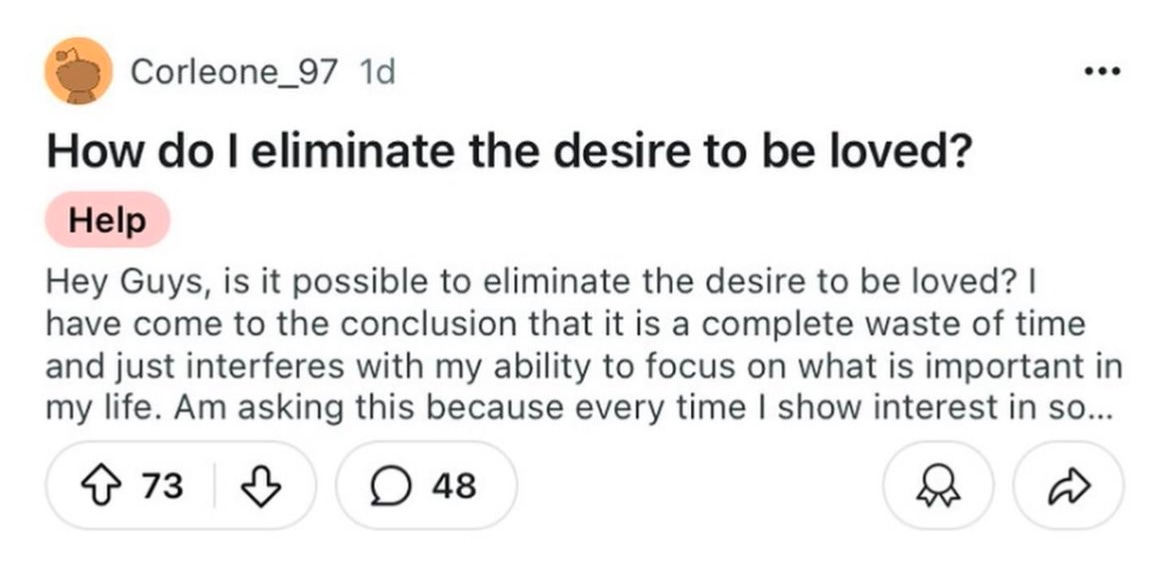

One day, towards the end of last year, the above screenshot appeared on my Instagram feed. “How do I eliminate the desire to be loved?” was its plaintive question; my initial response was a wry smile, lapsing into sympathetic, slightly amused, pity. It seemed almost ridiculous that anybody would seek instruction for an endeavour I considered so fruitless, and yet my heart went out to the poor Redditor. After all, their predicament was one I knew well: too many of my teenage years were spent longing for love while simultaneously longing to care less about it. I can certainly sympathise with the circumstances that cause someone to ask such a question, even if I’m not as desperate for an answer anymore. Still, I began to think: if we eliminate the desire to be loved, what else are we losing? Is it even possible to rid ourselves of it, and should we try?

Immediately I am inclined to say that the desire to be loved can’t be stamped out by sheer force of will. Rather, love is one of humankind’s innate, predetermined needs — our hunger for it is natural and undeniable. Consider Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: love and belonging, like safety and physiological functioning, are necessary; we desire them not out of some personal flaw but because we are hard-wired to do so.1 Besides, love comes with its own set of evolutionary benefits: it ensures that people care for us when we’re sick or injured; that they look for us when we leave and don’t return, whether out of fear for our wellbeing or simply because they miss our presence; even that they make us laugh, which is hugely beneficial for both the body and mind.2 Love, and I don’t just mean the romantic kind, keeps us safe — and on top of that, it keeps us happy. The desire for it is deep-rooted in our nature for good reason, and, try as we might, it’s a skin we can’t shed.

I’m not sure I even believe that we should try at all. The desire to be loved is not a “waste of time,” but a necessary precursor to genuine connection and companionship. It doesn’t interfere with our ability to focus on what’s important in life — love is what’s important (among other things, of course). Relationships of all kinds fulfil us in a way that almost nothing can emulate. I can think of little else that compares to a warm embrace, a kind word of encouragement, the singular thrill of spending time with someone who’s gladly chosen to spend theirs with you; I can think of little else more priceless than to know and be known, to support and be supported, to value and be valued. Being with people you truly connect with makes being alive feel good — it makes being yourself feel good. In the right company, everything feels a little more bright and little more bearable.

That, I think, is where the danger lies. Sure, these deep connections are all-important, but it’s easy for their pursuit to become all-consuming when you crave a quick fix for dissatisfaction. When I was younger, sick of myself and my life, it was instinctive to turn and seek a cure in others, to spend interminable nights obsessed with the thought of that warm embrace, that word of encouragement, that thrill of being chosen, and to believe that in these things lay the contentment I lacked. After all, love — the romantic kind in particular — has the curious power to make us feel like we matter; to be selected as the object of another’s affections, to be singled out as the recipient of a sentiment that goes far beyond polite tolerance, seems like proof that we’re worth something. Our right to take up space, regardless of our relationship status, is often lost to us; we crave concrete evidence, a lover’s smile like a permission slip granting us the privilege of breathing the same air as everyone else.

At some point in our lives, many of us fall or have fallen prey to the idea that being loved will make us happy, will make us make peace with ourselves. We chase after it panting like dogs and hang on white-knuckled to keep it — and yet, in time, the happiness we expected is overshadowed by the insidious fear of loss. We begin to worry: what if I’m not good enough for them? What if I’m a bother, or a bore? What if they stop loving me? We grow preoccupied by potential catastrophes and schemes to preserve the love we’ve found, because if it’s the only thing sustaining us, to lose it is to lose ourselves. There’s no denying that love can bolster self-esteem tremendously, but I don’t think it can form the basis of it alone. I used to believe otherwise, was once convinced that it was enough, but then even the assurance of affection couldn’t make me feel truly content with myself — something was missing, a gap even love couldn’t fill — and I began to reconsider.

How is anyone to deal with a desire so heavy and overgrown? I still don’t know for sure. I’d be missing the point of my own essay if I recommended simply “focusing on yourself” as a magical cure-all, as convenient as flicking a switch. Yet I wonder if the desire to be loved could at least be moderated by showing a little love to ourselves. Of course this is no replacement for the affection of others, but I do think that the ability to look at least somewhat kindly upon yourself — doing your best to forgive your mistakes, looking after your mind and body, and holding back from criticising yourself too harshly — could quell the hunger just a little. Still, it’s no easy task. In my experience, accepting that other people aren’t the only ones who can (or should!) make you feel important seems impossible when you don’t think you’re up for the job yourself. I’m still yet to master the art of being kind to myself, but I’ve improved in leaps and bounds since the age of fifteen, and these days my desire to be loved is much less burdensome than it used to be — and if this can happen to me, it can happen to anyone else.

There’s plenty of joy to be found in being ourselves if we look for it. I’ve found it in things like taking myself out to cafes and art galleries, celebrating my achievements (no matter how microscopic or mundane), taking care of my wellbeing — things that, ultimately, lead back to seeing myself as valuable. Feeling good about who we are (especially as a result of our own thoughts and actions, as opposed to the attitudes of others) is, I think, another one of those predetermined necessities, running parallel to the desire to be loved. Neither should be neglected or overemphasised. Still, getting along with ourselves is crucial: the people in our lives will come and go, but we have to stick with ourselves forever, so the sooner we learn to put up with ourselves, the better. The people around us are meant to complement us, not complete us; believing that we’re anything but whole without the adoration of others has never done anyone any favours.

All this to say: I think that to eliminate the desire to be love is to eliminate an essential element of our humanity. Without the drive to seek out genuine intimacy with others, whether as potential romantic partners or friends or something else entirely, we would be terribly lonely. Those of us who feel terribly lonely already will only alienate themselves further from this intimacy if they see their longing for it as a weakness rather than a symptom of being human; to turn from it is to sink deeper into isolation and believe that this will have to be enough — but it doesn’t. The fact that we can’t rid ourselves of the desire to be loved speaks volumes about its importance. There’s no point in feeling ashamed of being human, because we’re never going to be anything else — the desire to be loved is simply part of the package.

Of course, there are times when it expands monstrously, eating away at our capacity to enjoy everything else life has to offer — but love isn’t the sole source of fulfilment, as much as it may seem otherwise. This is something I’ve had to remind myself at various points throughout my nineteen years, but I’m getting better at remembering it nowadays. Whether or not desire to be loved can be shrunk back down to a less cumbersome size, for good, remains a mystery to me; the wisest course of action I can think of is to find those other things that make life worth living and to hang onto them tight: the sunset walks and hours by the sea, the music and movies and literature, the creative projects and personal growth (whatever that looks like for you). In time, the power of these things will expand too, and maybe someday the desire to be loved won’t feel as gargantuan as it once did. Maybe the void that love was supposed to fill won’t seem quite so empty.

Rod McKuen wrote "there is no misery in not being loved, only in not loving" I often think about his words. I guess that's the other way too of focusing on ourselves, seeing the value of love being not just about the receiving but something to do with the capacity we have for love. If we decided to be cured of the need for it, do we also lose something more valuable? And yet the vulnerability of that position is pretty uncomfortable...

Thanks for a thoughtful read!

you are so wise to be so young. i am crying on the train so thank you for this <3